Snapshots of a Cold War Childhood

- Terri Favro

- Feb 27, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Feb 28, 2022

Back in the Before Times, around 2013, an essay I'd written about growing up in Cold War Niagara was published in a U.K. journal called THE RED LINE., taking first place in their END OF THE WORLD writing competition. Snapshots of a Cold War Childhood was a memoir of nuclear paranoia, a bit of dark-humoured nostalgia about the long-ago tropes of that era of fear and optimism, mirrored by the increasingly sophisticated cameras that my father used to document our lives from the fifties to the eighties. Published when the Doomsday Clock of the Atomic Scientists was set at a mildly reassuring five minutes to midnight, this essay eventually mutated into a series of books: the novels Sputnik's Children and The Sisters Sputnik, as well as Generation Robot: A Century of Science Fiction, Fact, and Speculation. Sadly, the world-ending threat described in this almost-10-years-old essay has raised its ugly head once again. As I write these words, on February 27, 2022, 11:18 Eastern Time, the hands of the Doomsday Clock is set at a terrifying 100 seconds to midnight.

Snapshots of a Cold War Childhood

Snapshot number one is a black-and-white taken with a Kodak Brownie StarFlash. My

three siblings are horsing around at the edge of the Niagara Gorge so, by process of

elimination, that dazed looking baby stuffed into the stroller must be me. Mom waves a

blurred hand in front of her face like a starlet shooing away a pesky photographer. On

the picnic table beside her stands a sweating tallboy of Old Vienna beer – Dad must have

set it down, mid-swig, to snap the picture. You can see the Bridal Veil Falls, better known as the American Falls, in the distance.

I was born in the middle of the big, fat fifties, a decade stuffed with lardy

piecrusts, fluffernutters and fear. With the hands of the Doomsday Clock at two minutes

to midnight, I picked the wrong time to be born, and the wrong place: the Niagara

Peninsula may have seemed a sleepy backwater, all fruit farms and factories, but as my

father pointed out, “We’ll be the first to go.” His favourite magazine, Popular Science,

said that nearby Niagara Falls was a first-strike target for the Soviets because the hydro

generating station provided power to America’s eastern seaboard.

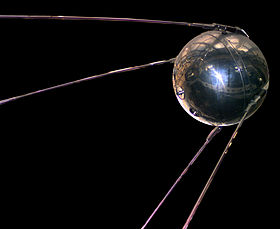

The possibility of death from above was a grey thundercloud on the robin’s-egg blue

sky of my childhood, starting with the basketball-sized Soviet satellite, Sputnik. We

were born about a year apart: I, on October fifteenth, nineteen-fifty-six, Sputnik, on

October fourth, nineteen-fifty-seven. I had barely blown out the candles on my first

birthday cake when the Soviets were at it again, launching poor little Laika the dog on

Sputnik II.

Down on Earth, I slept my cozy baby sleep, my capitalist cats curled in a box,

safe from being blown into orbit. But the grown-ups had bigger worries than pets in

space: the Soviets had the jump on us. They not only had the A-bomb, but, with Sputnik,

eyes in the sky. Canada’s Civil Defense Department erected air raid sirens and delivered

red-and-black flyers with a checklist to help us turn our cold cellars into bomb shelters:

canned goods, radio, water, first aid kit. And they explained how to brace yourself for a

nuclear attack: crouch against a good, solid wall and put your arms over your head.

I enjoyed looking at the drawings of the nuclear family in the preparedness flyer,

the little girl taking cover in her crinoline dress. I guessed that the Russians had attacked

while she was on her way to a birthday party.

“What happens if we can’t find the cats when it’s time to hide?” I asked my

mother as she hung laundry near the cherry tree where my grandfather sprayed pesticide

from a rusting tank on his back.

My mother spat out the clothespins she held in her mouth, and answered, “We’ll

have to leave the cats to fend for themselves, dear.”

I ran crying into our house. That was my last memory of the fifties. I awoke to the

sixties like Dorothy walking out of a black-and-white Kansas into a Kodachrome Oz that

promised all the future possibilities my brother and I saw in Popular Science. Flying cars.

Jet packs. Silver jumpsuits. I was especially looking forward to the moving sidewalks

because the worms couldn’t slither out onto them after rainstorms.

Snapshot two, taken with a Kodak Instamatic: white cake, white candles, starched ruffles

on my dress. My laughter reveals Pepsodent-perfect baby teeth. Unsmiling on either side

of me, my grandparents look as weather-beaten as Roman ruins. Having left behind the

dangers of one homeland, they must be pondering what to do about the iron sharks

swimming in the sky. Saving their family won’t be as easy as boarding a ship this time.

Everyone’s favourite NASA scientist, Wernher Von Braun, began appearing on

Disney’s Wonderful World of Colour to prepare us for the World of Tomorrow. In hisstiff Prussian accent, he explained the chall enge of escaping Earth’s atmosphere -- “Und now Goofy and Pluto vill enter the Mercury rocket…but look, they are veightless!” The space race was the happy flipside on the long-play record of the nuclear arms build-up. We knew that if the superpowers blew up the Earth, we could escape to the Moon.

Snapshot three: my brother in the cockpit of a B-52 Bomber constructed from pieces of

scrap wood, hanging by a rope from the crossbar of our clothesline pole. It must have

been back-to-school time: grapevines are visible in the background, the fruit almost

ready for picking.

I blew out six candles on the same day U.S. spy planes spotted Soviet missile

silos in Cuba. The American President waited a week to reveal this secret to the rest of us. Gathered in the TV room, we learned that the world was on the brink of total annihilation.

In a twinkling, the Americans went to DEFCON 2 –– “Their highest danger

level,” my brother explained. “The B-52s have been scrambled. It’s just a matter of time

until Mutual Assured Destruction.” I could see his ears pinking up with excitement.

“What does that mean?” I asked.

“Everybody dies,” he answered.

I thought this sounded like a poorly plotted Action Comic until the church parking

lot next door began to overflow with cars, even though it was only a Thursday. My

brother and I went to the cold cellar to play board games – The Game of Life, Lie

Detector, Concentration –– and wait for the end of the world. Why waste time on

homework if we were going to die anyway?

Our father came down and ordered us to hit the books, which turned out to be a

good thing; by Sunday the Russians had backed down. On Monday morning, we were in

school, the church parking lot as empty as a roller skating rink. It was the way things

were in those days: we’d tiptoe up to the edge of the abyss, then dance away again.

Snapshot four: Nuns look on as my class performs the Mexican Hat Dance in the school

gymnasium, commemorating the Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Air raid drills started in earnest. Our grade one teacher took us into the darkened

hallways of our pre-fabricated elementary school and told us to crouch down and cover

our heads. “Pray,” she said. “Pretend that the bombs are coming.”

I did as I was told, working myself into a panic, rushing through my Hail Marys.

I imagined I could hear the up-down, up-down wailing of the town’s air raid siren.

I sniffed a sudden bathroom smell as one of the boys, pressed against the wall

beside me, peed his pants.

Afterwards, we all went home for a hot lunch.

Snapshot five: A Yogi Bear punching bag looks on as my brother, sister and I watch TV.

Dad is still using the Kodak Instamatic, a workhorse of a camera.

High-pitched as a dentist’s drill, a thirty-second tone bled into our Saturday

morning cartoons, followed by a voice reassuring us that this was a test, this was only a

test. If this were a real emergency, you would receive instructions for Southern Ontario

and the Niagara Frontier.

We knew that the Emergency Broadcast System tone would be the last thing we’d

hear before atomic light flooded our cellars and crawlspaces, before our retinas scorched

and our irradiated skin sloughed off like wet play dough One day, the alert would be

real, but until then we could go back to laughing at the hapless Russian spies Boris and

Natasha on The Rocky & Bullwinkle Show.

On hot summer nights, our town’s air raid siren would go off by accident –– often

enough, that my father told us to ignore it. I’d call out, “I’m scared!” and my father

would yell: “It’s a malfunction! Go back to sleep!”

I worried that the Emergency Broadcast System voice was telling us what to do. I

left my bed and turned on the TV, but all I saw was the late news from Buffalo.

A concerned voice wanted to know: It’s 11 o’clock -- do you know where your

children are?

Snap six should have been a home movie of us at Wasaga Beach, shot with my father’s

Bolex 8-millimetre movie camera. Instead, it features unknown children (two boys, one

girl) riding bikes in a naked-looking subdivision. Half-built split levels sprawl behind

yards covered in bare earth. The trees are shorter than the kids.

Nuclear annihilation was not our only childhood worry. We also feared being

overrun by Communists, of having to conform to their grey, uniform sameness. My

brother bought second-hand comic books from the ‘fifties that imagined an alternate

history in which North America had fallen to Khrushchev. The stories were about

teachers being brainwashed and mothers being taken away from their children and sent

off to work on collective farms.

It was clear that, if Communism took hold, it was all over for our almost

American way of life. Never again would we enjoy a carefree holiday at Wasaga Beach,

as captured on my father’s new home movie camera. But when he sent in our film for

processing, instead of us at the beach, Kodak mailed back a movie of skinny kids

hamming it up on bikes. We had no idea who or where they were. My father spliced it

onto our vacation reel just the same; why waste film? The kids looked like us, anyway:

same haircuts, same clothes, same eyeglasses. No wonder the guys in the lab got people’s

home movies mixed up.

Snap eight was taken with a Polaroid Land Camera by my brother-in-law, who was

almost a priest but instead decided to marry my sister and write computer code. A

diorama of Neil Armstrong stepping down from the Lunar Lander is set up in lobby of the brake lining plant where our father worked. Armstrong looks oddly carefree. A sign says he is on loan from Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum of Niagara Falls.

The hands of the Doomsday Clock kept moving, sometimes closer to midnight,

sometimes further away. Through it all, crew-cutted angels with Texan accents rose to

Heaven and fell to Earth.

Mercury. Gemini. Apollo. We never missed a mission, kneeling in the TV’s

yellow glow with our processed cheese sandwiches and tumblers of Tang. We would

watch the familiar ritual of the booster rocket detaching itself and falling away, the men

with their white shirts and pocket protectors and black glasses, applauding and hooting

and throwing ballpoints in the air. Best of all, we’d see the astronauts themselves, their

easy, confident voices speaking to us from the soundlessness of space.

On Christmas Eve, nineteen-sixty-eight, Apollo Eight entered lunar orbit, went

around the Moon a few times, and came home. “Just a test drive,” my father explained.

“No fancy stuff.”

Astronauts Anders, Lovell and Borman read from the Book of Genesis to let the

whole world know that humans had a new home: In the beginning, God created the

Heaven and the Earth…

As they read the familiar words, we saw cheese-shaped slices of the Moon

through the pie-shaped window of the capsule, tantalizingly close.

That following summer, when Neil Armstrong’s puffy foot stepped down into the

lunar dust, followed by a bouncing Buzz Aldrin, it was almost anticlimactic. Afterwards,

my brother and I rushed outside to watch explosions of red-white-blue fireworks at the

church next door, as if God was celebrating the dawn of an era when humans could stand

a few million miles closer to Heaven and take Kodachromes of the Earth, tourists in the

Sea of Tranquility. We stretched out on lawn chairs and faced the stars, talking of space

stations and lunar colonies. Our enemy beaten, we knew our destiny was to get off the

Earth and live on the Moon.

What a surprise, then, to be Earthbound all these years.

Our dreams of space exploration – if we dream them at all – are measured now.

Cautious. Realistic. Who wants to risk the dangers of a mission to Mars when we can

watch robots rove the red surface from our cellphones?

The only way for me to get back that sense of space age adventure is to look at

old snapshots and home movies. They we are, flying scrap wood B-52s bombers, or

space-walking through the back yard, pretending to be Shepherd or Glenn or poor dead

Gus Grissom.

But as children of the cold war, that hopeful picture of life in space was scribbled

over with visions of Armageddon. Having gobbled up paranoia with our breakfast cereal

every morning, we grew up quietly believing that something deadly was about to fall on

us out of the sky.

Not the bomb anymore, of course. Just something.

Even though the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists sets the hands of the Doomsday

Clock at a slightly alarming five minutes to midnight, we no longer worry about Mutual

Assured Destruction –– also known as the end of the world. Our fears today are smaller

and more diverse.

We’re anxious about our children, who can’t go exploring without an escort. They

live indoor lives, isolated in the safety of climate-controlled homes. Many of them never

see the stars.

We’re terrified of our bodies, which betray us by growing a little bit older every

day. This deterioration was never supposed to happen to us, inheritors of an everyouthful,

candy-coloured, jet-packed future.

We’re afraid of our enemies – if only we knew who they were. One thing is sure:

like Communists, some of them live among us, hidden in plain sight.

We’re afraid of money. Not just how hard it is to make it, but how easy it is to

lose it. To our surprise, it doesn’t grow on trees.

And the trees are in trouble, too, the old Earth being stripped, poisoned and

slowly cooked to death, like a medieval saint.

Welcome to the anxiety-ridden World of Tomorrow, complete with the occasional

moving sidewalk, but without the lunar geodesic domes, silver jumpsuits or unflagging

faith in progress.

When one lonely air raid siren was discovered on a Toronto rooftop a few

summers ago, it was treated with a combination of amusement and nostalgia. A relic of a

long-forgotten time.

But I haven’t forgotten. Not really. Fear acquired in childhood is like muscle

memory. Like playing an arpeggio, or twirling a baton. Practiced long enough, it hardens

into a habit you never lose.

Comments